Massive Open Online Courses and Intellectual Property Rights Issues

Authors: Oana M. Driha & Vicente Zafrilla (University of Alicante)

1. Abstract

The explosive growth of the Massive Open Online Courses (MOOCs) in its early years points MOOC phenomenon to a very fast maturity. This new educative model is characterized by the absence of physical boundaries and open to anybody that wants to enrol in the course. Conversely, Intellectual Property Rights (IPRs) are territorial rights whose scope depends on national legislations, despite a certain degree of harmonization by virtue of international agreements. Therefore MOOC´s promoters and/or creators must take into account not only their national IPR legislation but also the international IPR framework. This paper aims to give an overview of the most relevant IPR issues from a EU and US perspective, namely copyright exceptions, ownership and authorisation and delivery of contents including copyleft based models and the so called Open Educational Resources. Moreover, some insights from the pilot MOOCs developed under the umbrella of BizMOOC are stipulated.

2. Introduction

The open science/Science 2.0 is a systemic change in the modus operandi of science and research affecting that affects the whole research cycle and its stakeholders (Burgelman et al., 2015). It is easily extendable to the educational system as a whole, including research and teaching tasks. The evolution of digital technologies, the rising expectations of citizens and the increased pressure on the Higher Education (HE) system to address the challenges faced by the society in recent years (since the Grate Recession onwards), among others, enabled this process since the beginning. As a matter of fact, it is a simultaneous process involving the rise of open sources, collaborative knowledge production, Creative Commons, open innovation, collaborative economy, MOOCs and web 2.0.

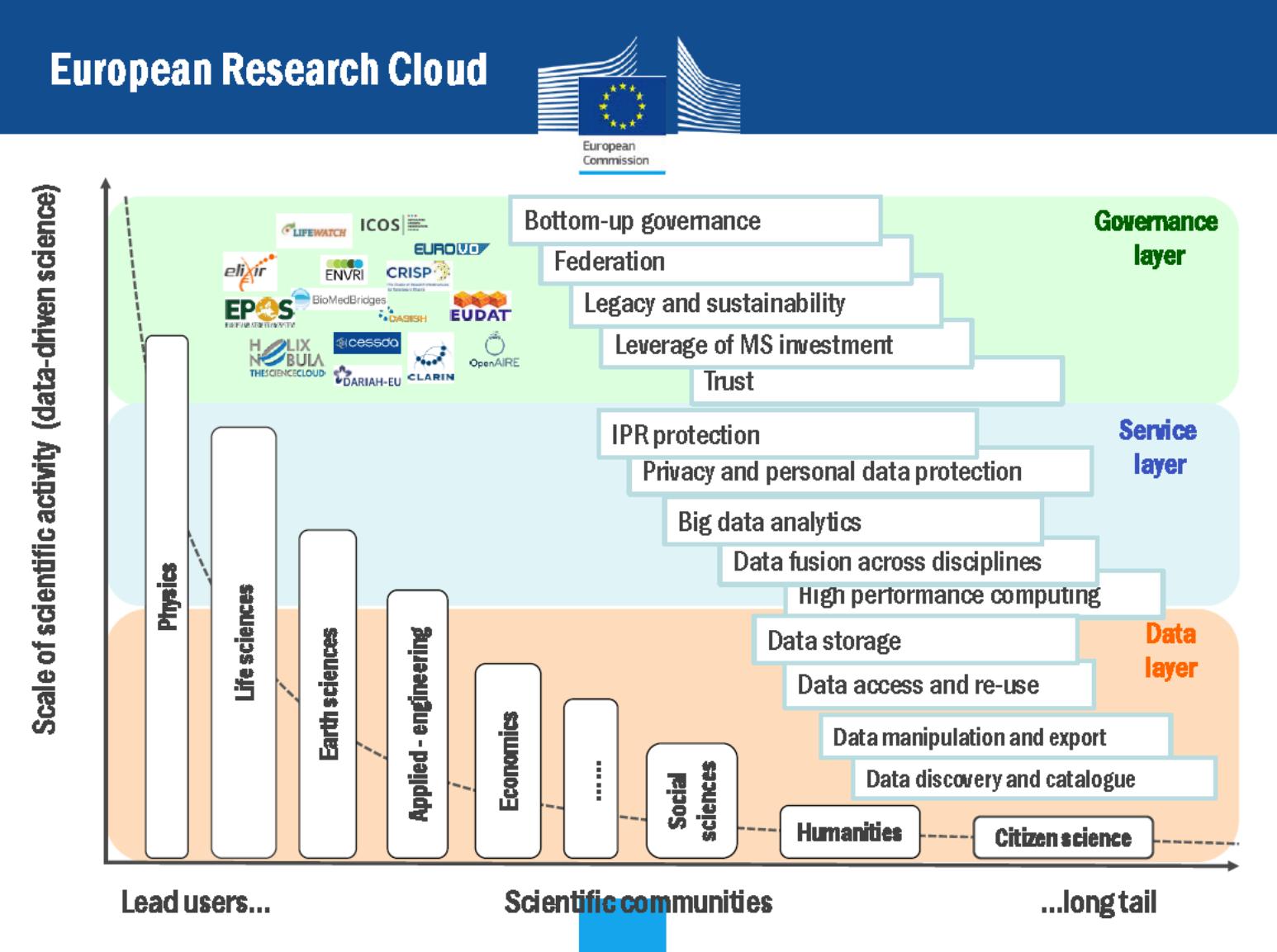

Within this process of openness of both science and teaching, intellectual property rights (IPR) protection plays a central role (see figure 1). In fact, open source licensing, compliance as well as participation can be complicated topics as understanding all the nuances of any of these tasks might require years of study and experience, and the success of doing things right is still not guaranteed (Haff, 2018).

Burgelman et al. (2015)

It must be highlighted that massive open online course (MOOC) phenomenon was created and highly replicated first in the US and then in Europe. Thus, the US higher education institutions (HEIs) and MOOC companies (main MOOC providers of platforms and courses) that leaded such innovation have bigger experience and better or at least more advanced strategies in creating and running MOOCs. This is so that MOOC platforms such as Coursera, Udacity and edX, for example, have all launched in 2011, the same year the concept was born due to Sebastian Thrus, lecturer of Computer Science at Stanford University (US). This new trend and diversification strategy requested by the changes experienced by the society and its needs in learning new skills and knowledge for the changing labour market, generated great interest in higher education and society, but also in the press (http://www.nytimes.com/2012/07/18/education/top-universities-test-the-online-appeal-of-free.html?_r=0) setting out a possible and innovative way for providing education at a rather low cost for millions of learners all around the world.

MOOCs are online courses designed for large number of participants, that can be accessed by anyone anywhere, as long as they have an Internet connection. MOOCs are open to everyone without entry qualifications, and offer a full/complete course experience online for free. This means that whatever is presented, taught, created and shared under a MOOC umbrella can be used and exploited be anyone with no limitations. MOOCs, as open contents, imply different activities, supervised by an instructor, with clear learning objectives limited in time (Hollands and Tirthali, 2014). For this several aspects are needed as follows (Chen, Barnett & Stephens, 2013):

- Software, registration, curriculum and assessment;

- Communication including interaction, collaboration, and sharing;

- Learning environment.

A characteristic of MOOCs is the free access to the complete course offering for all participants. However the materials are to be read, used and even reused up to a certain extent (Wahid et al., 2015). Such practices have direct implications concerning Intellectual Property Rights and namely copyright that will be analysed within this paper.

There is no doubt that legal framework and community model are fundamental in the process of developing source software aiming at obtaining a productive participation of users. According to Haff (2018), “You won’t know—and aren’t expected to know—everything at first”. But a good sequence of initial steps could be the following:

- Be aware that it is a “learning by doing process”

- Asking the right questions

- Identifying the appropriate paths of access

- Finding the field(s) where expertise is required for a proper development

In what refers to MOOCs and IPR some differences might be underlined, depending on their type there are some specific aspects to be considered like, for example who´s entitled to share of the rights of courses prepared for massive audience by faculty members that move from one institution to another (Starmsheim, 2014) as generally the materials used are designed by the instructors/professors. Meanwhile, for cMOOCs the situation might be even more complicated as materials already developed might be employed not just for the initial stage of the course, but also for the interactive and collaborative activities developed (and many times leaded) by participants (enrolees).

3. IPRs concerns and priorities for MOOCs

The rapid expansion in the use of online learning or e-learning and the development of Massive Open Online Courses (MOOCs) made possible providing content, data from tests, quizzes, exams, forum discussion, feedback asked, tutoring needed, etc. for students in any educational environment at global level. The evolution of information and communication technology, the shifts in the higher education sphere and the huge use of interactive digital technologies gave the opportunity to a huge community of learners from very different cultures and settings with a wide range of individual experiences, abilities and skills to get involved as an active part of in global level courses (Draffan et al., 2015).

Under these circumstances, many prestigious or less prestigious higher education institutions (at national and/or international level) decided to involve their academics in this new innovative teaching/learning methodology. Academics have to adapt the content and connected activities, included in a complete course experience, for online use, make use of authoring tools – in a rather different way than in research and traditional teaching materials –, media players and application systems needed for the browsers that display the content. Thus, new challenges must be faced by the education system as ensuring quality control, acceptance of copyright, academic probity and accessibility of materials have to be reshaped according to the new context and role of the knowledge demand (learners) and supply (educational system generally). It is the hosting university the one in charge of handling all these aspects.

Universities administrators often have to initiate new copyright policymaking in order to support and guide the development of MOOCs (Crew, 2014). The each time more globalised market and the increasing competitiveness in all aspects and sectors conducted to increasing legal need of large organisations. In the case of higher education institutions the new trends experienced due to the evolution of ICT, of the society and the economy it self, aspects traditionally handled individually, as ownership of teaching and research materials, sometimes have to be centralized.

These aspects and their trend lately, including the risks, opportunities and responsibilities linked to copyright, conducted to a shifts of the decision making regarding teaching and researching from the private offices of faculty members to a central one (Crew, 2014).

Different copyright priorities are highlighted in the US higher education system, as depicted in the table 1 below, from institutional policy on fair use, open access, etc. to individual copyright aspects.

| Nº | Priorities |

| 1 | Institutional Policy Development on fair use, open access, publication agreements, etc. |

| 2 | Copyright education for faculty and others. |

| 3 | Development of Information Resources (e.g. websites and other original materials). |

| 4 | Negotiating and Drafting Agreements and Licenses, notably for the acquisition of databases and library resources. |

| 5 | Individual Copyright Transactions and Queries, arriving daily (via phone, email and in person). |

| 6 | National and international Advocacy on copyright developments in legislatures, courts and other governmental agencies. |

| 7 | Original Research and Conference Presentations, sharing copyright knowledge and insights at meetings and through publications. |

| 8 | Professional Leadership in regional, national and international associations and events. |

Table 1. Copyright priorities. Source: Crew (2014).

Ever since MOOCs emerged a new trend was established in the online learning as a large number of universities all over the world accepted this new methodology of knowledge delivering. At the same time, outsourcing companies started to offer the infrastructure required. Despite the tremendous evolution of information and communication technologies and the each time wider options to share knowledge and works online, copyright issues started to experience considerable shifts when sharing and using knowledge and works shared online. A clear awareness on the copyright issues and the strategies that could be used to provide a secure and positive MOOC environment are needed.

When developing a MOOC there are two main IPR concerns that must be taken into account beforehand. The first one is choosing what information, lessons and materials will be included within the MOOC and what are the rights that the MOOC´s promoter has over them. The second is to decide under what terms will the materials be shared to users.

Am I entitled to include a fragment of a book within my MOOC? Under what terms? What happens if one of the experts that I have hired to develop the MOOCs contents starts to use it outside the framework of the MOOC?

As per the selection of contents and the rights over them it should be taken into account that Berne Convention (http://www.wipo.int/treaties/en/text.jsp?file_id=283698#P85_10661), to which United States and EU countries are members, states that copyright will protect, from the moment of its creation and without the need of registration “every production in the literary, scientific and artistic domain, whatever may be the mode or form of its expression”.

Thus, any extract from books or websites, photos or videos used in the MOOC is protected by copyright. Consequently it is very important for the promoters to assess if they are entitled to use third parties’ content that are planning to include in the MOOC (copyright clearance). It is also relevant to define the terms of the license and/or transfer of rights over the content created by third parties and in-house staff.

What really happens with the information we facilitate online? Once you upload your materials online in just one minute the information may get to thousands of other persons (see Intel image below).

Source: Intel, www.intel.com, extracted from https://es.scribd.com/doc/207956432/EMOOCs-2014-Policy-Track-4-Pongratz

Source: Intel, www.intel.com, extracted from https://es.scribd.com/doc/207956432/EMOOCs-2014-Policy-Track-4-Pongratz

It is important to decide under what terms will the users be authorised to use or replicate the copyright protected content. As we stated previously, the MOOC content must be deemed a “work” which is under copyright protection. Hence, the right holder (i.e. the MOOC promoter or creator) is entitled to prohibit the distribution, communication to the public and reproduction (among others) of such content without its consent both in Europe and United States (See art. 106 and ss. US Copyright Law http://www.copyright.gov/title17/92chap1.pdf and art 2 to 4 Directive 2001/29/CE on the harmonisation of certain aspects of copyright and related rights in the information society http://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:32001L0029&from=ES).

The “open” nature of MOOCs does not imply, therefore, that contents displayed or used during the course are freely available without restrictions for users.

On the other hand, a very restrictive policy on use of materials and content may lead to a poor leverage of the MOOC by users and may also limit the benefits that the MOOC may obtain from the works that alumni may develop over MOOC’s contents, namely derivative works.

Consequently, it is capital to design a content policy that allows balancing the commercial and academic interests of the MOOC´s promoters with the sufficient rights of access and use for MOOC´s users in order to reach the optimum level of dissemination, replication and knowledge “payback”.

4. Applying copyright exceptions and limitations to MOOCs

4.1. Brief introduction

Copyright over a work cannot be understood as an absolute right. Since the very beginning copyright related treaties such as Berne Convention (http://www.wipo.int/treaties/en/text.jsp?file_id=283698#P85_10661), the Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS) (TRIPS Agreement https://www.wto.org/english/tratop_e/trips_e/t_agm0_e.htm) or WIPO Copyright Treaty (WCT) (WIPO Copyright Treaty http://www.wipo.int/wipolex/en/treaties/text.jsp?file_id=295157) among others, have provided for the possibility for members to establish a series of limitations and exceptions over copyright. Whereas limitations are referred to subject matter that does no require copyright protection (e.g. legislative texts), exceptions are based in the nature of the use (e.g. quotation of a fragment) (Based on Ricketson (2003)). Both limitations and exceptions may be subject to certain requirements.

Additionally, the case law and doctrine from Courts have defined certain types of uses that cannot be prohibited by the copyright holders since they no fall within the scope of their exclusive rights.

In the following subsections we will examine if MOOCs can benefit from copyright exceptions both in EU and US.

4.2. Fair use and Teaching Exception

While in the US fair use is rather common, in Europe, the classic authors of right doctrine consider it to be an oxymoron or even a taboo (Hugenholtz and Senftleben, 2011). Traditionally, the use of third parties works for teaching purposes had been authorised under the fair use (US) and the teaching exception (EU).

4.2.1. Fair use in the US

US Copyright Law, according to its § 107. permits “the fair use of a copyrighted work, including such use by reproduction in copies or phonorecords or by any other means specified by that section, for purposes such as criticism, comment, news reporting, teaching (including multiple copies for classroom use), scholarship, or research, is not an infringement of copyright. In determining whether the use made of a work in any particular case is a fair use the factors to be considered shall include:

- The purpose and character of the use, including whether such use is of a commercial nature or is for nonprofit educational purposes;

- The nature of the copyrighted work;

- The amount and substantiality of the portion used in relation to the copyrighted work as a whole; and

- The effect of the use upon the potential market for or value of the copyrighted work.

The fact that a work is unpublished shall not itself bar a finding of fair use if such finding is made upon consideration of all the above factors“.

MOOCs introduce certain differences to traditional means of classroom-based teaching, which should make us to be reluctant or at least careful when deciding whether or not using third parties’ protected works. Some of these differences rely on the nature of the MOOC itself, such as being profit or not profit or the (larger) potential number of users. Others strongly depend on how the content is used (e.g. for mere decorative purposes) and how is delivered to users (e.g. only during the presentation).

It should be taken into account that according to the US Supreme Court Doctrine the commercial character does not preclude automatically the application of the fair use exception (See Case Campbell vs Acuff Rose No. 92/1992 (1994), among others https://www.law.cornell.edu/supct/html/92-1292.ZO.html).

The positions concerning the use of use of copyright works in MOOCs under the umbrella of fair use doctrine in US go from total opposition “that exception does not apply to unmediated, no-credit MOOCs that are open to the public” (Lauren Schoenthaler, senior University counsel. More information available here: http://www.stanforddaily.com/2012/11/01/intellectual-property-concerns-for-moocs-persist/) to more favourable ones “Assuming materials are used in reasonable amounts, and that they are not materials created and marketed specifically for in-class use, a traditional four-factor analysis should be favourable (sic) for most instructional uses of educational content on MOOC platforms (From Butler (2012) p.6)”.

Even though in doctrine it is not clear if MOOCs can benefit from the fair use exception, in practice some of the most relevant institutions involved in large-scale MOOCs production understand that “the conditions that govern whether you can use it in a Berkeley classroom are different from those that govern whether MOOC students outside Berkeley are allowed to use it (Berkeley: Copyright and Trademark Issues https://berkeleyx.berkeley.edu/wiki/copyright)“ or “Fair Use can apply to MOOC courses, but in a more limited fashion than in more traditional educational environments.” (Arizona State University. Copyright: Copyright and MOOCS http://libguides.asu.edu/copyright/gfa)

Furthermore, there are other stakeholders that discourage the use of third parties’ works “Fair use in the context of open access online courses is limited and should be relied upon as a last resort (Columbia University https://copyright.columbia.edu/content/dam/copyright/copyright%20guidelines%20open%20online%20courses%20moocs%20(00201903-4x9672E).pdf)” or “Coursera’s copyright guidelines for instructors strongly discourage the use of third party copyrighted materials” (Duke University Libraries Drawing the Blueprint As We Build: Setting Up a Library-based Copyright and Permissions Service for MOOCs http://www.dlib.org/dlib/july13/fowler/07fowler.print.html).

4.2.2. Teaching exception in the European Union

The teaching exception in Europe is much more restrictive. According to article 5.3.a) of 2001/29/CE Directive on the harmonisation of certain aspects of copyright and related rights in the information society (Copyright Directive) (Directive 2001/29/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 22 May 2001 on the harmonisation of certain aspects of copyright and related rights in the information society http://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=OJ:L:2001:167:0010:0019:EN:PDF).

5.3. Member States may provide for exceptions or limitations to the rights provided for in Articles 2 and 3 in the following cases:

(a) Use for the sole purpose of illustration for teaching or scientific research, as long as the source, including the author’s name, is indicated, unless this turns out to be impossible and to the extent justified by the non-commercial purpose to be achieved

At first glance, the EU teaching exception extends to rights of reproduction and communication to the public but also to distribution as long it is necessary for the reproduction purposes according to article 5.4 of the Copyright Directive (Art 5.4 of the Copyright Directive. Member states “may provide similarly for an exception or limitation to the right of distribution as referred to in Article 4 to the extent justified by the purpose of the authorised act of reproduction”). Moreover, this exception only applies in case of non-commercial purposes, which notably limits the type of MOOCs that may benefit from this exception.

As if the question was not tricky enough, it must be taken into account that the Directive does not oblige to Member States to include such exception. This together with the different drafts and interpretations that Member States did over the teaching exception lead to an wide variety of teaching exceptions that may, or may not, cover the use of protected works in MOOC under the teaching exception subject to certain conditions. “In short, only a few domestic teaching exceptions (Italy, Germany, Luxembourg, and the Netherlands) may cover –to some extent- digital distance education; Most of them (Austria, Belgium, Switzerland, Ireland and the U.K., let alone, Spain, France and Portugal) do not cover DDE, or are uncertain (the rest)” (From Xalabarder (2004)).

4.2.3. Applicability of Fair use and/or teaching exception to MOOCs

With a view to the abovementioned, and to be practical, it is not advisable to rely in none of these exceptions when using third parties protected content. As a general rule, it is advisable to keep third parties protected content to a minimum and/or get the consent prior to include the content within the MOOC.

To benefit from fair use and teaching exceptions a case-by-case study it is almost mandatory, study that must take into account inter alia the nature of the work, the type of use, the commercial or non-commercial purpose as well as the geographical scope, since certain types of use covered by the fair use exception in the US may not be covered by the teaching exception in the EU, and even uses under the teaching exception in a given EU country may not be covered in another.

4.3. The § 110.2 US Copyright Act exception

Fortunately, in 2002 the Technology, Education, and Copyright Harmonization Act, Public Law 107-273, (hereinafter TEACH Act) modified sec. 110 of the US Copyright Act to give legal coverage to certain teaching uses in a digital environment.

Sec 110.2 TEACH Act establishes that they are not copyright infringement, what is to say, they do not require prior consent from the right holder the following uses by or in the course of a transmission:

- The performance of a non-dramatic literary or musical work or reasonable and limited portions of any other work;

- The display of a work in an amount comparable to that, which is typically displayed in the course of a live classroom session.

That exception is subject to a number of requirements, namely, that it does not apply to works “produced or marketed primarily for performance or display as part of mediated instructional activities transmitted via digital networks” nor to copies that were not lawfully made or acquired (Secc 110 TEACH Act: if the institution knew or have reasons to knew to believe it was not lawfully made and acquired).

As per the subjective requirements, only governmental bodies or accredited non-profit educational institutions can benefit from this exception. In addition, the uses are allowed as far as they are “at the direction of, or under the actual supervision of an instructor as an integral part of a class session offered as a regular part of the systematic mediated instructional activities”.

There are also subjective restrictions concerning who could be the beneficiaries of this exception: the students enrolled in the course and the officers or employees as part of their official duties or employment.

Finally, the transmitting institution needs to take appropriate measures to ensure the respect to third parties’ copyright such as technological measures to limit the access or inform about the protected nature of the works.

4.4. Use of links to websites

Another practice that is common in MOOCs is to provide links to third parties’ websites that include copyright protected content. May these practices be considered copyright infringement?

The answer is no. Under different reasoning Courts’ doctrine in both United States (http://cases.justia.com/federal/district-courts/new-york/nysdce/1:2011cv05052/382350/99/0.pdf?ts=1411563493) and Europe (http://curia.europa.eu/juris/celex.jsf?celex=62012CJ0466&lang1=es&type=TXT&ancre=) coincide in that mere linking does not constitute an infringement of copyright by itself.

The only care it should be taken when including links within MOOC’s materials is to ensure not to link to illicit content, including copyright infringing content. Thus, it is advisable to provide links from trusted sources or even to the author´s/right holder website.

5. Strategies for content use

Once we have examined what can and what cannot do with third parties’ protected works without authorisation it is time to choose what strategy and type of materials will be included within a MOOC.

The different types of contents that can be used are summed-up in the table below.

| Strategy | Advantages | Disadvantages |

| Use own original materials | ||

| Materials: | ||

- Books, journals articles, photos, images, slides, films that you created yourself in which the copyright is yours.

- Video: there can be different rights available.

- Music and images used within a video are called background IPR while acts captured in the video such as a lecture are foreground rights. The author will often hold the foreground right while the background rights belong to the person or company who created the IPR originally. Thus, copyright clearance must be done before it could be used (Kernohan, 2014).

No copyright issues generally.

- Time consuming

- Costly to produce original materials for every course.

Seek Permission from Copyright OwnerWhen third party materials are shared in MOOC, the content provider must first ask for permission from the copyright owners. Thus, email or request for copyright owner will be needed.Less time is needed for developing the materials.

- Long process (on average around 3 months).

- Sometimes may involve certain payment or conditions.

Utilize Materials in the Public DomainUse works that is in the public domain which are free from copyright protection (Courtney, 2013).Even attribution is not required although such is appreciated.Some constrains on how public domain works can be used. The exception is basically based on common sense where works cannot be used in a way that may be considered offensive, unless it is consented (Pixabay, 2015).Use materials under the General License TermsUse work that has been offered to public via unrestricted license such as the GNU Lesser General Public License (LGPL) or Creative Commons (Udacity have made its video courses available in YouTube under Creative Commons 3.0 license. Thus, the videos can be viewed and shared for non-commercial purposes (Carr, 2013). MIT and Harvard aim to make much of the edX course content available under more open license terms. This will allow them to create a vibrant ecosystem of contributors and further edX’s goal of making education accessible and affordable to the world (Cheverie, 2013).) (CC) licensing systems (Courtney 2013).Allows online content to be shared and even adapted by other users (Clement, 2013).Not all general/copyleft licenses allow all types of uses (e.g. derivative works) or purposes (e.g. commercial purposes)

Table 2. Types of contents: advantages and disadvantages. Source: based on Wahid et al. (2015).

After running the pilot MOOCs developed and implemented under BizMOOC umbrella, it must be underlined that, in line with Kernohan (2014) the use of own original materials was the case of MOOC1 – “Learning to learn” and MOOC3 – “Entrepreneurship and sense of initiative” showed to be considerably time consuming and rather Costly to produce original materials.

For MOOC2 – “How to generate innovative ideas and how to make them work” the time needed for developing the materials and the expertise available in the topic were more limited. Hence, and despite the clear advantage of not having any copyright issues generally when producing own materials, materials already developed and existing online were selected. Seeking permission from copyright owners was essential, but then the selection process was not that short as it might be though beforehand. Thus, the majority of materials used in this case were under the General License Terms, mainly under creative commons. This way, the team in charge of this MOOC it took advantage of the possibility of sharing and even adapting contents available online to the course designed as (Clement, 2013).

In both MOOC2 and MOOC3 participants were expected to contribute through cooperative activities to co-creating contents of these two MOOCs. In this case of MOOC2, despite including a module dedicated to IPR and MOOCs, not many users were familiar enough with IPR, nor to the extent to which materials already available online could be used for the MOOC´s activities. Therefore, this might be an issue to be faced mainly in cMOOCs and hMOOCs if participants are not felling well prepared or confortable enough in these IPR issues.

5.1. Use or develop own materials

5.1.1. Authorship versus ownership

Prior to analyse the copyright implications concerning the development of materials it should be taken into account that copyright grants two types of rights; moral rights and economic rights.

Moral rights belong to the author and are non-transferrable. The main ones are the right to be recognised as author or the right to the integrity of the work.

Economic rights grant the author (or owner) the right to prevent third parties from: communicating to the public reproducing, distributing and transforming the work, among others. Economic rights can be transferred or licensed in order to allow third parties to exploit the work.

Hence, we must differentiate between author (or creator), who owns the moral rights and may also own the economic rights, and owner (or right holder) that owns or have the right to exploit economic rights by virtue of law, a transfer of rights or a license.

5.1.2. Determining the ownership

The ownership of course content can have significant legal consequences when they are created with the aim of being distributed to a public audience, commercialized or licensed to a third party for distribution. The key issue is to determine who is the owner of the economic rights over the different contents and over the MOOC itself.

According to the degree to which institutional resources are used in the creation of online courses materials, the university could establish their ownership. Creating online materials may entail a significant investment of university resources through institutionally licensed software, instructional and web designers, videographers, teaching assistants and administrative support. In this case, the university could claim the ownership as a result of its significant contribution to the creation of course materials (The Intellectual Property Policy of Indiana University considers online instructional materials as traditional works owned by the faculty member except if they were specifically commissioned or created using “exceptional” university support.).

The applicable copyright law, the university policy and individual agreements terms are the most relevant elements when determining the ownership of courses content.

Since MOOCs´ usually involve more than one person, different institutions and, very likely, different countries, it is not advisable to rely in the terms stated on general provisions of the copyright laws, which, for example, might differ from the country of origin of the author to the country where the organizing university is based.

Hence, the most effective tools to ensure that the university is the owner of the contents, or, at least, has authorisation enough to include them within its MOOC, is to create a solid policy on course ownership and/or to sign individual agreements with all those stakeholders not covered under the scope of such policy (e.g. external experts).

A. University Policies on Course Ownership

Traditionally copyright policies, concerning courses´ ownership are divided into two different trends: the work for hire doctrine or the academic tradition.

- The institutions own the academic work of their employees, as course materials are prepared within the scope of the faculty member’s teaching duties. Some institutions follow the “work for hire” doctrine, providing that works made during the scope of the creator’s employment belong to his or her employer (This would be the case of the University of Virginia, of the Stanford University or of the University of Chicago, for example).

- The employees of the institution are the owners of their academic work, which may include course materials, if the work is not a specifically commissioned work or funded by grants (See the case of Carnegie Mellon University (Intellectual Property Policy from 1985), which allows the creator to retain all rights to “educational courseware”. More recently, the University of Michigan (2002) transfers university copyright to faculty for scholarly works, citing as examples lecture notes and case examples. University of Texas considers that multimedia courseware products and distance learning materials are a jointly authored work, owned by both the university and the faculty member (System “Regents’ Rules and Regulations” from 2002). In 2008, the University of Minnesota, in its “Copyright Policy: Background and Resource Page”, stated that faculty member owns copyright to all academic works, specifically identifying online materials created by a faculty member. Once the MOOC phenomenon was born, the University of North Carolina stipulated in its Policy Manual that “traditional work or non-directed work” might include fixed lecture notes and distance learning materials).

According to Pierson et al. (2013), a more practical framework for managing online courses could be assured through a policy framework that acknowledges the interests of various stakeholders and unbundled the traditional rights associated with ownership. In this line, there are mainly two options: (a) the creator(s) have a license to use the materials for personal non-profit educational and research purposes even after the creator(s) leave the university; (b) the license is retained by the university and any commercial use have to be approved by the university based on the conflict of interest policy of the institution.

B. Individual agreements

In order to avoid uncertainty regarding ownership, many HEIs entered into contracts with instructors previous to the development of online courses. Like this, course production expectations are clearer, as well as faculty concerns about pedagogy and control of content when working with third-party content hosting providers. The relationship between faculty members (involved in online courses production) and hosting providers must be clearly defined, especially in terms of its status as a for-profit or non-profit entity.

Sometimes the hosting provider signs an agreement with the instructor(s) and/or its institution. That might be an online course development agreement or instructional policies and guidelines. The aspects that must be considered for this kind of agreement are:

- Ownership and rights of the Instructor;

- Joint Works;

- Warranty/Third-Party Contributions;

- Course Development;

- Technology Standards and Tools;

- Instruction;

- Resources;

- Compensation/Teaching Credit;

- Royalties and Revenue Sharing;

- Term of course and reruns;

- Approval;

- Compliance Requirements.

5.1.3. Potential conflict of interest and commitment concerns

What could cause a conflict of interest? A simple example could be a full time professor focusing his/her time in a different activity that is not educational and research programmes of the university. Traditional policies of conflicts of interest at higher education institutions often address the ownership of teaching at other institutions or the time a staff member should dedicate to outside consulting activities. With the online teaching, there is not just one approach, but the policy is generally including the same elements as the one applicable to consulting activity involving research:

- Consulting activities and the associated agreements must be consistent with university policies;

- Faculty should disclose to the university all consulting activities as required under university policy;

- Faculty should inform the party for whom they are consulting of the faculty member’s obligations under the university’s intellectual property and conflict of interest policies.

Additionally, some other limitations may be appropriate in the teaching context regarding the following aspects:

- Outside Teaching;

- Creation of course materials for third parties;

- Use of University Resources and Personnel;

- Limits on Consulting Time;

- Management Role or Equity Interest in Hosting Provider;

- Exploitation of the University Brand.

5.2. Getting permission from third parties

5.2.1. Introduction

Besides the creation of its own content, it may be interesting or even necessary to include third parties´ works in the MOOC, for example a fragment of a video or an article. In all those cases not covered by the exceptions and limitations included in point 3 (see above) or any other applicable exception require prior authorisation from the owner of the work.

5.2.2. Individual consent: Licensing

A. Licensing Agreements

In some cases, the authorisation should be requested individually to the owner of the work, usually by means of a license agreement. The main disadvantages that individual licensing entails is that it is rather slow and usually entails the payment of royalties to the owners.

There are some key issues that should be included within the License Agreement.

- Work affected by the agreement

- Rights that are being granted and the modality: according to the type of use of the work (e.g. it is not the same to reproduce a fragment during a lesson that deliver a copy of the entire work to each student)

- Reservation of rights.

- Exclusiveness (or not).

- Territory: in most of the cases a general license over all territories will be necessary

- Time extension

- Price

- Termination and Liability clauses

- Applicable law and jurisdiction and/or arbitration

B. Terms and conditions

In many universities students own the intellectual property rights of their papers and project except when for their creation significant university resources were necessary (i.e., labs, high tech equipment, special funding, grants, etc.). In this line, the majority of the web site owners requires their users to provide a non-exclusive use license to any intellectual property that the user deposits on the website or platform.

| Platform | Terms and conditions |

| Coursera | The Sites may provide you with the ability to upload certain information, text, or materials, including without limitation, any information, text or materials you post on the Sites’ public forums such as the wiki or the discussion forums (“User Content”). With respect to User Content you submit or otherwise make available in connection with your use of the Site, and subject to the Privacy Policy, you grant Coursera and the Participating Institutions a fully transferable, worldwide, perpetual, royalty-free and non-exclusive license to use, distribute, sublicense, reproduce, modify, adapt, publicly perform and publicly display such User Content. To the extent that you provide User Content, you represent and warrant to Coursera and the Participating Institutions that (a) you have all necessary rights, licenses and/or clearances to provide and use User Content and permit Coursera and the Participating Institutions to use such User Content as provided above; (b) such User Content is accurate and reasonably complete; (c) as between you and Coursera, you shall be responsible for the payment of any third party fees related to the provision and use of such User Content and (d) such User Content does not and will not infringe or misappropriate any third party rights (including without limitation privacy, publicity, intellectual property and any other proprietary rights, such as copyright, trademark and patent rights) or constitute a fraudulent statement or misrepresentation or unfair business practice. |

| edX | User Postings Representations and Warranties. By submitting or distributing your User Postings, you affirm, represent and warrant (1) that you have the necessary rights, licenses, consents and/or permissions to reproduce and publish the User Postings and to authorize edX and its users to reproduce, modify, publish and otherwise use and distribute your User Postings in a manner consistent with the licenses granted by you below, and (2) that neither your submission of your User Postings nor the exercise of the licenses granted below will infringe or violate the rights of any third party. You, and not edX, are solely responsible for your User Postings and the consequences of posting or publishing them. License Grant to edX. By submitting or distributing User Postings to the Site, you hereby grant to edX a worldwide, non-exclusive, transferable, assignable, sublicensable, fully paid-up, royalty-free, perpetual, irrevocable right and license to host, transfer, display, perform, reproduce, modify, distribute, re-distribute, relicense and otherwise use, make |

| Udacity | With respect to any User Content you submit to Udacity (including for inclusion on the Class Sites or Online Courses) or that is otherwise made available to Udacity, you hereby grant Udacity an irrevocable, worldwide, perpetual, royalty- free and non-exclusive license to use, distribute, reproduce, modify, adapt, publicly perform and publicly display such User Content on the Class Sites or in the Online Courses or otherwise exploit the User Content, with the right to sublicense such rights (to multiple tiers), for any purpose (including for any commercial purpose); except that, with regard to User Content comprised of a subtitle, caption or translation of Content, you agree that the license granted to Udacity above shall be exclusive. |

Table 4. Policy regarding users creation : Coursera, edX and Udacity. Source: based on EDUCAUSE (Joan Cheverie) and Pierson et al. (2013).

5.2.3. Open content

Another possibility is to use third parties’ works that have been delivered under Open Content terms or a general- copyleft license.

According to the David Wiley´s definition of Open Content (http://www.opencontent.org/definition/) it describes any work that grants users a perpetual authorization to (5rs’ rule):

- Retain – the right to make, own, and control copies of the content (e.g., download, duplicate, store, and manage)

- Reuse – the right to use the content in a wide range of ways (e.g., in a class, in a study group, on a website, in a video)

- Revise – the right to adapt, adjust, modify, or alter the content itself (e.g., translate the content into another language)

- Remix – the right to combine the original or revised content with other material to create something new (e.g., incorporate the content into a mashup)

- Redistribute – the right to share copies of the original content, your revisions, or your remixes with others (e.g., give a copy of the content to a friend)

Examples of Open Content are content distributed under Creative Commons-BY, Apache or BSD licenses (Berkeley Software Distribution).

On the other hand, the term “copyleft” comprises a number of general licenses that allow the use of the protected works under certain conditions without the need of an individual authorization. In other words, every user that fulfils the terms defined in the general license is automatically granted a license over the content.

There is controversy concerning the “open” nature of copyleft licenses between those that consider that open content must only be referred to the works shared under the 5rs’ rule and those that prefer to understand that limitations only make such works “less open”. Examples of this type of licenses are GNU GPL and LGPL (Lesser GPL). For the purposes of this article we are going to differentiate between “open” referred to all the content that meets the all 5rs’ rule and “less open” to the content under a general license that partially limits one or more of the 5rs´.

B. Creative Commons Licenses (https://creativecommons.org/)

There are different types of copyleft licenses according to the different conditions that them entail. In this section we are going to examine one of the most widespread copyleft licenses in the world. Creative Commons is a flexible system that allows authors or owners to offer general license under one or more of the following conditions:

- BY- Attribution: any third party using the work must credit the author.

- ND- Non- Derivative: derivative works (i.e. modified, improved or translated versions) are not authorised.

- SA- ShareAlike: any derivative work must be shared under the same conditions of the original work.

- NC- Non- Commercial: the work cannot be used for commercial purposes.

- These conditions could be mixed into different types of Creative Commons Licenses (see table below).

| CC Licenses | Terms and conditions |

| CC BY: Attribution | |

| CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike | |

| CC BY-ND: Attribution-NoDerivatives | |

| CC BY-NC Attribution-NonCommercial | |

| CC BY-NC-SA: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike | |

| CC BY-NC-ND: Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs |

Table 5. Terms and conditions. Source: based on Creative Commons (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/?lang=en)

5.3. Public Domain content

Public Domain is composed by every work whose copyright term has expired. There are a number of considerations that should be taken into account when using public domain works:

The term of protection for copyright works may differ from country to country. As a general rule, the term of duration is, at least, the life of the author plus fifty years, according to Berne Convention (Berne Convention: http://www.wipo.int/treaties/en/text.jsp?file_id=283698). However the term in US and Europe tends to be longer (usually the life of the author plus seventy years).

Second, it must be noted that works within Public Domain may still be subject to copyright in certain cases (e.g. a translation of a work in the public domain is a derivative work that enjoys copyright protection) or to other related rights (e.g. a 2010 concert that includes a Vivaldi musical piece played by the London Philharmonic Orchestra is subject to their performance rights, even when Vivaldi´s works have fallen into Public Domain).

Finally, it is strongly advisable to credit the author. In United States crediting the author of a work in the public domain is optional and even a matter of etiquette. On the other side, in continental Europe the right to the recognition of the works’ authorship is closely linked to the “paternity” of the work and is perpetual (i.e. does not expire).

6. Delivering and sharing content

6.1. Introduction

The prior sections have been focused on the copyright concerns related to the works that are included within the MOOC. In this section we are going to focus on the legal alternatives when deciding to deliver the content to users.

There are two main trends: the first one is the so-called Open Educational Resources approach; the second is the traditional approach were rights of access, modification, reproduction or communication are limited by law or defined by the general terms and conditions of the MOOC.

6.2. Open models

In recent years, OER had experienced a boost and stakeholders and policy makers have highlighted their importance. The European Commission (From European Commission (2013)) has stressed the role of Technology and OER to increase efficiency and equity in education by “increasing the value of and potential for international cooperation”, “broadening access to education” or “alleviating costs for educational institutions and for students, especially among disadvantaged groups” among others.

The UNESCO adopted definition (From UNESCO (2011)) of Open Educational Resources is “(…) teaching, learning and research materials in any medium that reside in the public domain and have been released under an open licence that permits access, use, repurposing, reuse and redistribution by others with no or limited restrictions (…)” this definition was based on Hewlett Foundation definition (Atkins et al, 2007) and slightly differs from the original one “OER are teaching, learning, and research resources that reside in the public domain or have been released under an intellectual property license that permits their free use or re-purposing by others” (From Atkins et al (2007)).

Relationship between OER and MOOCs is still not well defined. Some affirm that MOOCs are part of the OER “There have been a variety of different approaches to OER including OpenCourseWare, Re-useable Learning Objects and Massively Open Online Courses (MOOC)” (From JISC “A guide to open educational resources” Retrieved from http://www.webarchive.org.uk/wayback/archive/20140614151619/http://www.jisc.ac.uk/publications/programmerelated/2013/Openeducationalresources.aspx#Manage) while others make a clear distinction between them “General rights for copying and repurposing are what make OER different from any other educational resources available online free of charge. Free materials and courses such as most MOOCs (Massive Open Online Courses) allow users only fair use rights, or rights stated in specific licenses issued by the publisher.” (From Grodecka, K. et al. (2014))

Under our point of view the latter definition is grounded on a narrow idea of MOOCs. It is true that the word “open” in MOOCs is mainly referred to the access to the course itself and does not extend to the content and the delivery of works. However nothing prevents a MOOC owner to deliver such materials under “open” or “less open” terms. Consequently, all those MOOCs whose contents are delivered under the terms stated within OER definition (i.e. open licence that permits access, use, repurposing, reuse and redistribution by others with no or limited restrictions) should be deemed an OER.

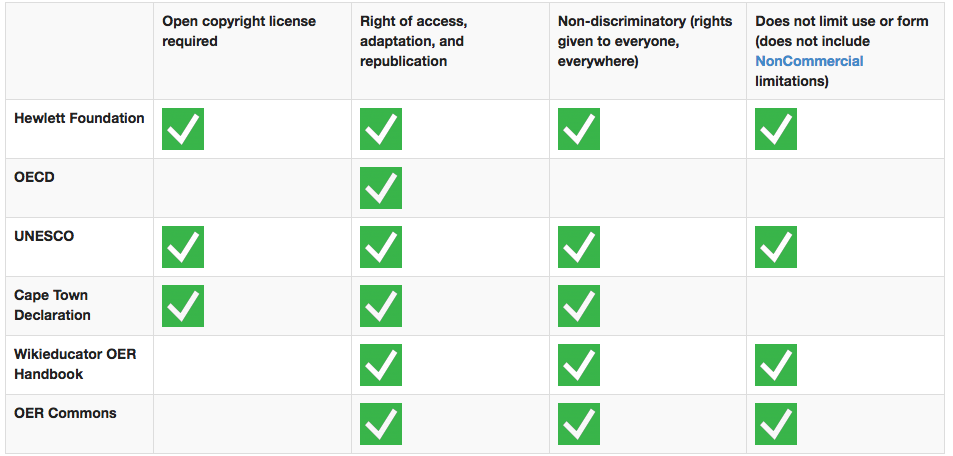

According to UNESCO’s OER definition the use, reuse or repurposing of OER should be available with “no or limited restrictions”. What should be understood as no or limited restrictions?

Source: Creative Commons by OER Portal under BY-CC 4.0 (From https://wiki.creativecommons.org/wiki/What_is_OER%3F)

Despite the variety of definitions, we can assume, with a view of their comparison that the “limited restrictions” refer only to Non-Commercial restrictions. Thus, MOOCs that include limits other than such limitation (e.g. Non-Derivative or ShareAlike) cannot be considered “open”. However, certain authors understand that ShareAlike restrictions reinforce the “openness” by compelling to project it to all derivative works “The ShareAlike condition make the openness stronger every time somebody re-uses resources under CC BY-SA, he or she is obliged to publish on the same conditions” (From Grodecka, K. et al. (2014)).

The main advantages associated to open models is a higher level of replicability and visibility, that lead to higher levels of engagement of the users with the update and adaptation of materials “People will often volunteer to do things you could never pay them enough money to do” (From Wiley, D. (2007)). In addition, contributions of users encourage the adaptation of the course to the most relevant areas of the topic, making the MOOC a true demand-driven service.

On the other side, releasing an open MOOC requires the prior definition of a sustainable business model which should be aligned with the university strategy and entails losing the control over how the contents are used and or adapted, making more difficult to verify the quality of derivative works.

6.3. Copyright-based models

Although every MOOC is open to a certain degree, at least with concerns the access to the course, there are MOOCs promoters that prefer to rely in copyright based models. This type of models are usually implemented through the inclusions of copyright clauses within the course’s terms and conditions such as the following:

| Platform | Terms and conditions |

| Coursera (Terms of Service) |

All content or other materials available on the Sites, including but not limited to code, images, text, layouts, arrangements, displays, illustrations, audio and video clips, HTML files and other content are the property of Coursera and/or its affiliates or licensors and are protected by copyright, patent and/or other proprietary intellectual property rights under the United States and foreign laws. In consideration for your agreement to the terms and conditions contained here, Coursera grants you a personal, non-exclusive, non-transferable license to access and use the Sites. You may download material from the Sites only for your own personal, non-commercial use. You may not otherwise copy, reproduce, retransmit, distribute, publish, commercially exploit or otherwise transfer any material, nor may you modify or create derivatives works of the material. The burden of determining that your use of any information, software or any other content on the Site is permissible rests with you. |

| edX (Terms of Service) |

Unless indicated as being in the public domain, the content on the Site is protected by United States and foreign copyright laws. Unless otherwise expressly stated on the Site, the texts, exams, video, images and other instructional materials provided with the courses offered on this Site are for your personal use in connection with those courses only. MIT and Harvard aim to make much of the edX course content available under more open license terms that will help create a vibrant ecosystem of contributors and further edX’s goal of making education accessible and affordable to the world. |

| Udacity (Terms of Service) |

Except as otherwise expressly permitted in these Terms of Use, you may not copy, sell, display, reproduce, publish, modify, create derivative works from, transfer, distribute or otherwise commercially exploit in any manner the Class Sites, Online Courses, or any Content. You may not reverse-engineer, decompile, disassemble or otherwise access the source code for any software that may be used to operate the Online Courses. Subject to your compliance with these Terms of Use, Udacity hereby grants you a freely revocable, worldwide, non- exclusive, non-transferable, non-sublicensable limited right and license (a) to access, internally use and display the Class Sites and Online Courses, including the Content, at your location solely as necessary to participate in the Online Courses as permitted hereunder, and (b) to download the Educational Content (as defined below) so that you may exercise the rights granted to you under Section 7 below. |

Table 5. Rights and permission to use the content offered by Coursera, edX and Udacity. Source: EDUCAUSE (Joan Cheverie).

This approach benefit from a higher level of control over the works and their derivatives, since any type of use not included within the terms and conditions is subject to prior authorisation. It also simplifies the process of verification of the materials.

On the other side, they tend to have a lower level of replication and require assuming additional costs in distribution and update of materials.

7. A note on hosting agreements and liabilities

The implementation and running of a MOOC needs not only to create the structure, methodology and content for the course, but also digital platform that supports the delivery of lessons, exercises and activities.

The alternatives for the universities are to create their own platform or to provide their MOOCs through already existing platforms. The second alternative is the most popular (Even top HEIs in the world prefer to use already existing platforms such as Coursera or edX instead creating their own platforms.) one since it is cheaper, more flexible and allows benefiting from the level of recognition of already existing MOOC’s platforms.

Generally the platform is selected depending on the goal of the courses. Additionally, the methodology and the distribution model of both university and host content provider should be taken into consideration when selecting the platform.

The platform provider acts in these cases as a hosting provider. Such position entails certain legal concerns that are going to we exposed in brief. First, it is important to define properly what are the rights and obligations of the platform provider, including the degree of control and access to the content, and to define them clearly in a hosting agreement. Hence, the following issues should be considered before signing an agreement with a content hosting provider:

- Content Ownership and Use;

- Content Placement;

- Content Selection, Modification and Removal;

- Attribution and Branding;

- Flexibility.

Second, the services of the platform provider may originate certain liabilities concerning copyright, which are usually limited by clearance clauses such as the two depicted below.

| Coursera “Copyright Clearance” | edX “Content” |

| As between University and Company, University will be responsible for reviewing and obtaining any necessary licenses, waivers or permissions with respect to any third-party rights to Content provided by University or Instructors. To the extent that Company provides any accommodations for the Content, as provided in Section 11.2 below, the Parties acknowledge and agree such accommodations are being provided solely to make such Content accessible to persons who otherwise would not be able to access or use such Content, and are not intended to be modifications to, or derivative works of, any underlying Content. | Institution will be responsible for ensuring that all content (including third party content contained in InstitutionX Courses) provided by Institution or its instructors to edX may be used and made available via the Platform, including without limitation, the edX.org website without infringing or violating any copyright or other intellectual property rights of any third party. EdX may take down content that is the subject of an actual or reasonably anticipated claim by a third party and, to the maximum extent permitted by applicable law, Institution will indemnify and hold edX harmless for any such claim. |

Table 6. Liabilities: courser versus edX. Source: Pierson et al. (2013).

8. Conclusions

With the new era of MOOCs, higher education institutions are facing many shifts not only in the methodology of sharing knowledge, but also in the way they have to protect the content of the courses taught through MOOCs.

Intellectual Property international legal framework still presents certain challenges to online courses delivered under MOOC´s structure. Nevertheless it is possible to deliver MOOCs without incurring on copyright liabilities by taking into account the main differences between US and EU as well as the general provisions of international treaties such as Berne Convention or WIPO Copyright Treaty.

It is worth noting that the exceptions to copyright in the US fair use doctrine substantially differ from the teaching exception in the EU. In general is not advisable to rely in the compatibility of these exceptions without a case-by-case assessment.

As per the creation of contents and the use of third parties content it is important to get the consent of the authors by means of a license or general terms and to ensure that such consent covers the different uses of the works in the MOOC. The deliverance of materials to users also has copyright implications, mainly related to the authorised uses (i.e. to read, to copy, to readapt, to repurpose etc.), which are usually included within copyright clauses on the general terms and conditions of the course.

Open Educational Resources approach, based on open or less open copyleft licenses, allow to reach higher levels of replicability and sustainability of the course in exchange of a reduction of the control over the content and materials, that may lead to validation of content challenges. Opting between traditional copyright based approach and OER approach is mostly a matter of business model that should be assessed by each institution in the framework of its general strategy.

Summing up, the risks of copyright infringement when sharing works in MOOCs are not to be taken lightly. Each person involved in this kind of courses, not just the content providers, but also the users and the platform providers, should be aware of the copyright issues and their potential vulnerability when using or sharing copyrighted materials. And form the BizMOOC pilot MOOCs it seems to be a tricky task as the IPR/copyright culture is still limited among the public.

Note

References

Atkins, D.E., Brown, J.S. & Hammond, A.L. (2007). “A Review of the Open Educational Resources (OER) Movement: Achievements, Challenges, and New Opportunities”. Hewlett Foundation. Retrieved from http://www.hewlett.org/uploads/files/ReviewoftheOERMovement.pdf

Butler, B. (2012) “Massive Open Online Courses: Legal and Policy Issues for Research Libraries”. Association of Research Libraries. Retrieved from http://www.arl.org/storage/documents/publications/issuebrief-mooc-22oct12.pdf

Clement, M., Ng, A., & Daniel, J. (2013). Coursera under fire in MOOCs licensing row.http://theconversation.com/coursera-under-fire-in- moocs-licensing-row-15534

Courtney, K. K. (2013). The MOOC syllabus blues Strategies for MOOCs and syllabus materials. College & Research Libraries News, 74(10), 514–517. http://crln.acrl.org/content/74/10/514

Crews, K.D., 2014. “The Growth of Copyright”, IPR info, Issue 2, IPR University Center, Helsinki, available at: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2457292

Draffan, E.A., Wald, M., Dickens, K., Zimmermann, G., Kelle, S., Miessengerger, K., Petz, A. (2015). “Stepwise Approach to Accessible MOOC Development”, in Assistive Technology: Building Bridges, Eds. C. Sik-Lányi,E.-J. Hoogerwerf,K. Miesenberger, IOS Press, Amsterdam.

EDUCAUSE http://www.educause.edu/blogs/cheverij/moocs-and-intellectual-property-ownership-and-use-rights

ENISA, 2010. “Online as soon as it happens”, Whitepaper of the European Network and Information Security Agency, ISBN-13: 978-92-9204-036-9.

European Commission (2013). “Communication on Opening up Education: Innovative teaching and learning for all through new Technologies and Open Educational Resources”. Brussels. Retrieved from http://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:52013DC0654&from=EN

Grodecka, K,. Sliwowski, K. (2014) “Open Educational Resources Mythbusting”. Open Educational Resources in Europe. Retrieved from http://mythbusting.oerpolicy.eu/wp-content/uploads/2014/11/OER_Mythbusting.pdf

Hugenholtz, P.B., Senftleben, M.F.R. 2011.“Fair use in Europe. In search of flexibilities”, http://www.ivir.nl/publicaties/download/912

Kernohan, D. (2013). Risky business: make sure your MOOCs aren‘t exposing you to legal challenge. Jisc Inform, 39, 14–19. Retrieved from https://www.jisc.ac.uk/blog/risky-business-make-sure-your-moocs-arent-exposing-you-to-legal-challenge-06-mar-2014#.U16DjLhdVoA

Pappano, L. The Year of the MOOC, N.Y. Times, Nov. 2, 2012, http://www.nytimes.com/2012/11/04/education/edlife/massive-open-online-courses-are-multiplying-at-a-rapid-pace.html?pagewanted=all&_r=0.

Pierson, M.W., Terrell, R.R., Wessel, M.F. (2013) “Massive Open Online Courses (MOOCs): Intelectuall Property and Related Issues”, The National Association of College and University Attorneys, Session 5G. Available at: http://www.higheredcompliance.org/resources/publications/AC2013_5G_MOOCsPartI1.pdf

Pixabay. (2015). Public Domain Images-What is allowed and what is not? Retrieved September 2, https://pixabay.com/en/blog/posts/public-domain-images-what-is-allowed-and-what-is-4/

Pongratz, H. 2014. “Talking about Data. Data ownership, ethics and intellectual property”, https://es.scribd.com/doc/207956432/EMOOCs-2014-Policy-Track-4-Pongratz

Ricketson, S. (2003). “WIPO Study on Limitations and Exceptions of Copyright and Related Rights in the Digital Environment”. WIPO. retrieved from http://www.wipo.int/edocs/mdocs/copyright/en/sccr_9/sccr_9_7.pdf

UNESCO and Commonwealth on Learning (2011, 2015). “Guidelines for Open Educational Information in Higher Education”. Paris. ISBN 978-1-894975-42-1

Xalabarder, R. (2004). “Copyright exceptions for teaching purposes in Europe”. UOC retrieved from https://in3.uoc.edu/opencms_portalin3/export/sites/default/galleries/docs/INTERDRET/Xalabarder_2004_CopyrightExceptionsForTeachingPurposes.pdf

Wahid, R., Sani, A.M., Mat B., Subhan, M., Saidin, K. (2015). “Sharing Works and Copyright Issues in Massive Open Online Courseware (MOOC)”, International Journal for Research in Emerging Science and Technology, vol. 2 (10), pp. 24-29.

Wiley, D. (2007). “On the Sustainability of Open Educational Resource Initiatives in Higher Education”. OECD. Retrieved from https://www1.oecd.org/edu/ceri/38645447.pdf

Webpages and blogs:

Copyright and Your classroom: http://ii.library.jhu.edu/2015/08/07/copyright-and-your-classroom/

Risky business: make sure your MOOCs aren’t exposing you to legal challenge, available at: https://www.jisc.ac.uk/blog/risky-business-make-sure-your-moocs-arent-exposing-you-to-legal-challenge-06-mar-2014

When MOOC Profs Move, available at: https://www.insidehighered.com/news/2014/03/18/if-mooc-instructor-moves-who-keeps-intellectual-property-rights

MOOCs – Your Legal Questions Answered, available at: https://as.exeter.ac.uk/media/level1/academicserviceswebsite/library/documents/copyright/JOSClegal_Guide_to_MOOCs_and_the_Law.pdf

Online courses raise intellectual property concerns, available at: http://www.stanforddaily.com/2012/11/01/intellectual-property-concerns-for-moocs-persist/