Existing MOOC business models

Authors: Thomas Staubitz (HPI), Darco Jansen (EADTU), and Michael Obrist (iversity)

1. Abstract

While Massive Open Online Courses (MOOCs) offer a complete course experience free of charge by definition, there are monetary cost and benefit associated with it. Several stakeholders are associated with the creation and the distribution of MOOCs as well as research and further services beyond the course itself. The diversity of MOOCs and their players makes it thus difficult to analyse a universal business model for MOOCs. Also, the growing influence of MOOCs attracts new stakeholders in the market, bringing in new services, sponsorships, customers, cross-financing models etc. This paper focuses on monetary costs as well as direct and indirect revenues of MOOCs and their associated services and offers further readings for related issues.

2. Introduction – Why do business models for MOOCs matter?

Although some providers are slowly changing this policy, many Massive Open Online Courses (MOOCs) are still offered completly for free online. The participants do not have to pay anything for a full course experience: all the resources and most of the course services (e.g. feedback, tests, quizzes, exam and some limited tutoring) are offered free of charge. But who is paying for the efforts in developing MOOCs and for all the operational costs?

To answer that question we need to look at possible business models describing the conceptual structure that supports the viability of a business (i.e. how an organisation fulfils its purpose including all business processes and policies). Business models can apply to any type of organisation including one at the governmental level (see for example chapter 8 of UNESCO-CO, 2016). For a long time, one of the main challenges in the area of MOOCs was to develop sustainable business models and to some extend it still is.

However, creating and analysing a general or ‘universal’ business model for MOOCs is difficult, if yet impossible. This is mainly due to the fact that several stakeholders are involved in the creation and the distribution of a course, as well as research and further services beyond the MOOC itself. The content of a course might come from a university, a company, a non-profit organisation or other parties. When it comes to the distribution, there are platforms that use content from external partners and generate revenue from issuing certification or additional services. Other platforms are either part of a higher education institution that provides the content or are funded by a third party. Thus, the conceptual differences of these various content providers, platforms and other stakeholders make it difficult to establish a universal MOOC-model. Therefore, we will first define our understanding of the roles of these stakeholders.

Additional servicesSome MOOCs make use of additional services that are mostly provided by specialised commercial companies. An example are online proctoring services to guarantee that the registered student has taken the exam herself and did not cheat.Mostly commercial companies

| Role | Description | Actor |

| Content provider | Provides the course content (slides, videos, quizzes, exams, reading material). This can be one party, or it can be split up between several parties. E.g. one party could produce the slides while another party records the videos, or one party produces week 1, while the other party produces week 2, etc. | Universities, enterprises, Commercial content agencies, NGOs, governmental institutions, associations |

| Platform provider | Hosts and operates the MMS. Provides the possibility to conduct courses either as a self-service product or with full support. | Commercial companies, universities, platform developers, non-profit organisations, enterprises, governmental institutions |

| Platform provider | Hosts and operates the MMS. Provides the possibility to conduct courses either as a self-service product or with full support. | Commercial companies, universities, platform developers, non-profit organisations, enterprises, governmental institutions |

| Certification provider | Some MOOCs offer more than the mostly rather informal MOOC certification. Examples are e.g. ECTS credits or professional certification. | Universities, enterprises, commercial companies, governmental institutions, associations |

Table 1:Possible roles of stakeholders in the realm of MOOCs

Often different roles are taken by the same actors. Depending on the current role, the actor might have different interests. We will now give a few examples to make these distinctions more tangible.

Coursera or edX are mainly platform providers. The content provided on their platforms is mostly offered by international top-ranking universities. They are also platform developers as they are actively developing their own MMSs. Both have some sort of university background, Stanford for Coursera and Harvard/MIT for edX. While Coursera is a privately funded commercial company, edX is a non-profit organization. While Coursera’s MMS is proprietary, edX has open-sourced their MMS software. Another example is the German Hasso Plattner Institute (HPI), the Digital Engineering faculty of the University of Potsdam. The HPI is operating its MOOC platform openHPI since 2012. Very soon they started to develop their own MMS, which is now also used e.g. by SAP, the German software enterprise and the World Health Organization (WHO). In the case of openHPI, the HPI covers all of the listed roles, content provider, platform provider, platform developer, certification provider, and even additional services (e.g. by providing the recording studio for customers). Here, we actually could even list two additional roles, which are MOOC researchers, and MOOC educators (teaching others how to MOOC). In the case of openSAP and OpenWHO, SAP as a global enterprise and the World Health Organization as an organisation of the United Nations, take the roles of content providers and platform providers, while the HPI serves as the platform developer (and MOOC researcher). Examples for MOOC platforms run by the government are

FUN (France Université Numerique https://www.fun-mooc.fr/) in France and Campus (https://campus.gov.il/) in Israel; both are using the open source MMS OPENedX.

3. Business Models and the Business Model Canvas

3.1. What are business models?

The ‘business model’ concept is a theoretical model being used in science and the business-context. Especially, the use of word ‘business’ appears to be confusing: although the concept was developed in the context of for-profit businesses, it is now applied to any type of organisation, including for-profit, non-profit,governmental or any other type of organisation. In addition, there are many versions of business models. Al-Debei (2008) identified four primary dimensions: (1) Value Proposition, (2) Value Network, (3) Value Architecture, and (4) Value Finance while Yoram (2014) comprised the following three components: (1) Customer Value Proposition; (2) Infrastructure (both resources and processes) and (3) Financial Aspects.

However, the economic models cannot be applied to open licence and free resources like Open Educational Resources (OERs) and some parts of MOOCs (Stancey, 2015). Stancey argues that the classic economy is based on scarcity while OERs and MOOCs are based on abundance at no cost. Thus, completely different approaches might be needed.

3.2. About the Business Model Canvas

With the aim to either develop a new one or document existing business models, many frameworks and templates are used. The most popular one used nowadays is the Business Model Canvas (Fielt, 2013). The Business Model Canvas was initially proposed by Osterwalder (2010) based on his earlier work on Business Model Ontology (Osterwalder, 2004). Since then, new canvases for specific niche markets have appeared, such as the Lean Canvas (https://leanstack.com/lean-canvas/) and Open Business Model Canvas (http://edtechfrontier.com/2015/12/08/converging-forces/). In addition, the latter includes ‘Social Good’ and ‘CC licence’ (https://docs.google.com/drawings/d/1QOIDa2qak7wZSSOa4Wv6qVMO77IwkKHN7CYyq0wHivs/edit) while the Lean Canvas is especially in the interests of the start-ups (https://canvanizer.com/how-to-use/business-model-canvas-vs-lean-canvas).

3.2.1 Components of the Business Model Canvas

The components of the canvas are:

- Value Propositions: A promise of value to be delivered and acknowledged and a belief of the customer that value will be delivered and experienced. A value proposition can apply to an entire organisation, parts thereof, customer accounts, or products or services.

- Customer Segments: What group(s) of customers is/are a company targeting with its product or service by applying filters such as age, gender, interests and spending habits.

- Channels: What channels does a company use to acquire, retain and continuously develop its customers.

- Customer Relationships: How does a company plan to build relationships with the customers it is serving.

- Revenue Streams: How is a company pulling all of the above elements together to create multiple revenue streams and generate continuous cash flow.

- Key Activities: The most important activities in executing a company’s value proposition.

- Key Resources: The resources that are necessary to create value for the customers. These resources could be human, financial, physical and intellectual.

- Key Partnerships: What strategic and cooperative partnerships does a company form to increase the scalability and efficiency of its business.

- Costs: What are the costs associated with each of the above elements and which components can be leveraged to reduce cost.

3.2.2. Applying the Business Model Canvas to MOOCs

As mentioned above, applying the Business Model Canvas (BMC) to MOOCs is not straightforward due to the high variability in concepts and the diversity of stakeholders involved in a course. The recent UNESCO-COL (2016) publication clearly demonstrates this and only gives some examples of BMC at governmental level. Since it is quite common that more than one business or organisation creates and distributes a MOOC, this paper suggests to just analyse the sub-goals of each stakeholder (e.g. the value proposition, customer relationship, key activities, partnerships and resources as well as the costs and revenues might be very different for each stakeholder). A possible common value proposition for all stakeholders could be, that a MOOC’s content brings additional knowledge and learnings to the participants. Considering the high variation of the different stakeholders with regard to the components of the BMC, this paper proposes a new model to analyse drivers behind the MOOC business with focuses on costs and revenues.

4. A model to illustrate phases of a MOOC, its various stakeholders and costs and revenues associated

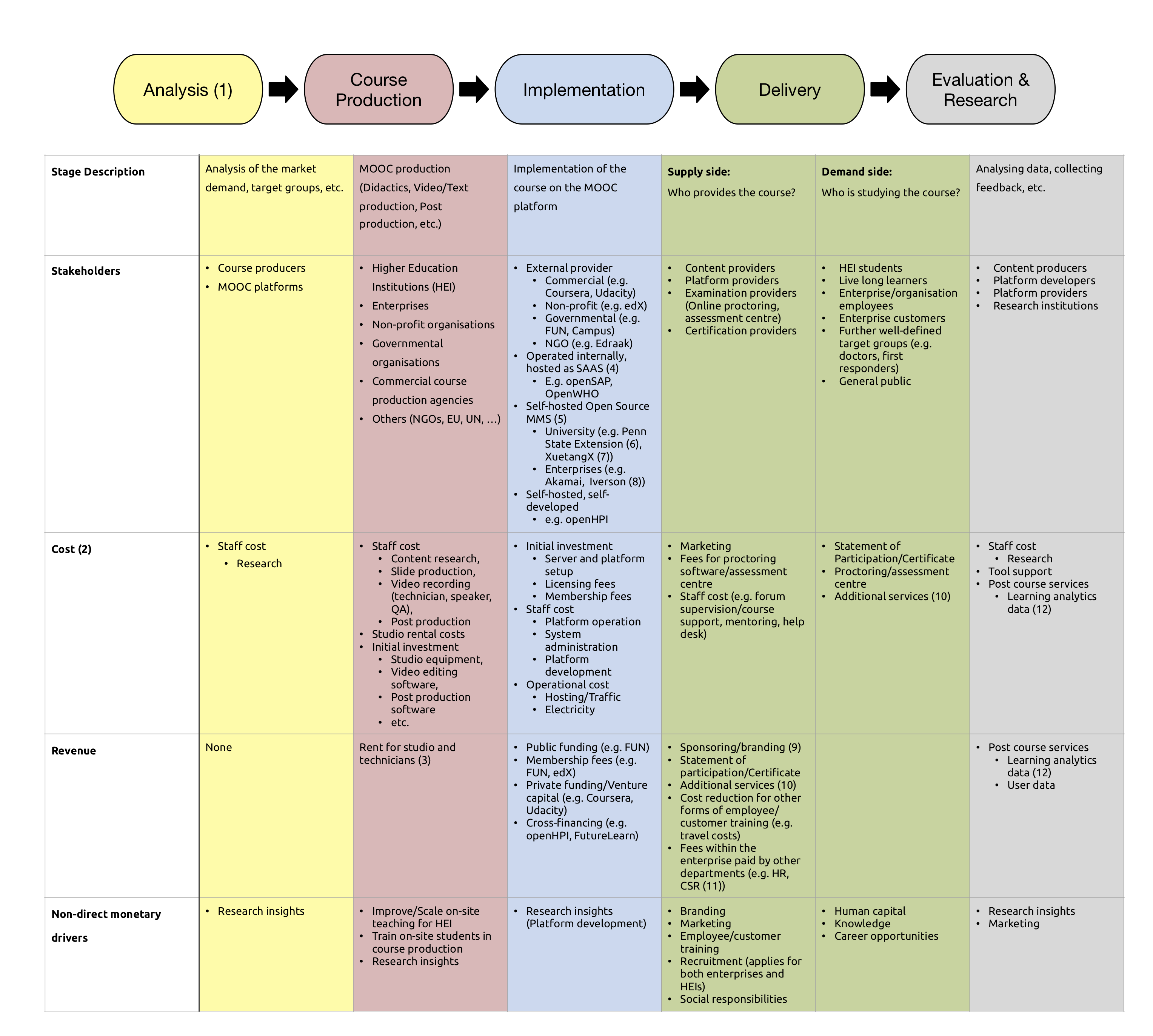

Table 2 presents a model that illustrates the involvements of various stakeholders in a MOOC’s different development phases, and their associated costs and revenues. (All cost/revenue go beyond the product of the MOOC itself. MOOCs are offered for free to learners; (2) Estimated cost of producing a MOOC vary a lot. For further information see section 4.1 – What are the general cost to produce a MOOC, and for some cost examples, click here; (3) Some examples of possible (to be paid for) services are discussed in section 4.2 and 4.4.2; (4) Some courses are sponsored by third parties such as companies, organisations etc. that are not directly or only partly involved in the course production.)

Table 2: A model to illustrate phases of a MOOC, its various stakeholders and costs and revenues

Source: Own illustration

This table only covers the main stakeholders, and their associated costs and revenues. The costs and revenues in each row reflect a stakeholder’s expected return and expenditure for that specific stage (Example: An NGO produces an online course in collaboration with a University and delivers this on an external MOOC platform. There are production cost for the NGO & the University as well as implementation cost for the MOOC platform. The MOOC content is free for learners, however the revenue from a Statement of Participation (SoP) and certificate sales are shared between all three parties.), company or organisation that provides the content and usually focus on the distribution of content (e.g. edX, coursera, iversity).). Thus, one could set up an individual business model for each stakeholder. Depending on the stakeholder’s role in the endeavour to analyse, its cost/revenue structure can differ substantially. One example for a differentiation could be the cost/revenue structure of a content provider and an external MOOC platform. While the content provider generates its cost mostly from course production and course delivery, an (external) MOOC platform (Meaning platforms that are not part of the HEI (Higher Education Institution), company or organisation that provides the content and usually focus on the distribution of content (e.g. edX, coursera, iversity).) not only spends most of its money on course implementation and distribution but also has higher (operational) fix cost, resulting from hosting and improving the platform. It is the usual case that the content/course providers (e.g., a university) receive funding or revenues from sources other than their MOOCs activities and cross-finance their MOOCs platform (Here it is not much of a difference if the university runs a self-hosted, open source or self-developed, MOOC platform or collaborates with an external provider, as all of these models have to be financed somehow). Therefore, their primary goal might not be making a profit with their MOOC programme but offering it for the needs of marketing, branding, recruiting, teaching (both onsite students, e.g. in the production of MOOCs as well as the actual MOOC participants as part of their social responsibility to provide a life-long-learning programme), and research.

Overall, it might be worth noting, that not only the absolute number of MOOCs is growing (A closer look at the growth of existing courses between 2011-2016 can be obtained by accessing the following link https://www.edsurge.com/news/2015-12-28-moocs-in-2015-breaking-down-the-numbers), but also an increasing number of new stakeholders are entering that market, resulting in the emergence of new cooperations, new services, sponsorships, customers, and cross-financing models, etc. in MOOCs.

A completely different approach to adapt the Business Model Canvas for MOOCs has been taken by (Alario-Hoyos 2014). They developed the MOOC Canvas (https://www.it.uc3m.es/calario/MOOCCanvas/documents/MOOCCanvas.png) as a framework to support content providers in making certain design decisions based on the platform to be used, and the human, intellectual, and equipment resources that are available.

5. Costs and possible revenues

5.1. What are the general costs to produce a MOOC?

The production and development for MOOCs varies a lot between courses. The amount of money invested is typically depending on factors such as:

- Staff cost

- Length of the MOOC (e.g. 4 weeks or 12 weeks)

- Hours of video material produced

- The production of further cost-intensive resources, such as graphs, animations, overlays etc.

- Post production services

- Existing knowledge and experience of the team

- Existing equipment

- Content availability prior to course production

The development costs for MOOCs are thus difficult to estimate. The numbers vary between $40.000 – $325.000 for each course, taking all costs into consideration (Hollands and Tirthali, 2014). Without taking staff cost and initial investment (studio etc.) cost into consideration, these numbers might be lower at times. In addition, about $10.000-$50.000 are needed as operational cost for teachers, assistants and mentors, for every course running on a MOOC platform.

Video production is often one of the major cost drivers. A report estimates a high quality video production cost of $4,300 per hour of finished video (https://www.cbcse.org/publications/moocs-expectations-and-reality). It turned out, however, that high-quality video is not necessarily what makes a great MOOC. Naturally, a certain minimum standard has to be kept: good audio quality, readable slides, visible speaker, etc. This can already be achieved for a far lower price. Depending on the number of videos to be produced, it makes perfect sense to invest some money in a small semi-professional studio. This studio also can be rented out to other course producers later on to counterbalance the initial investment. The Austrian platform iMoox, e.g., calculates with inhouse video production costs of about 390 Euros for a six-minute video, assuming that the recording of such a video will require 20 hours of technician time (Fischer, 2014). openHPI, in contrary, calculates with a recording time of 2-4 times of the video length, mostly depending on the lecturer’s experience. In addition to the technician’s time, the lecturer’s time and the time of a (second) content expert to supervise the recording shouldn’t be forgotten in the calculation. Additional costs are needed for the MOOC platform, either a fee (annual or per MOOC) for a partnership with a MOOC provider or the staff cost (development and administration) for a self-hosted solution. Further costs can arise for marketing, learner support, helpdesk, etc.

However, these estimates are based on research of mainly U.S. institutions offering their MOOCs to one of the main U.S. MOOC platforms. Experiments with different kinds of MOOCs and in other continents show that these costs can be reduced by:

- involving target audience in either development (young people learning to code) and/or operation of the MOOC (peer-to-peer assessment, p2p tutoring, etc.)

- providing MOOC on an institution’s own platform and not outsource it to one of the MOOC platforms.

- using open source software for MOOC platforms or use free (social media) tools of the internet

- cost efficient video recording tools

- use of existing material and OER or even re-use complete MOOCs from other institutions

- low-cost partnership for services that are scalable and at best to organise cross-institutionally.

Since many of the possible revenue sources have turned out not to cover the costs, but essentially MOOCs offer a complete course experience to learners for free. Since direct revenues from MOOC courses are often less than the cost to produce and host the courses, the costs are not (directly) paid by MOOCs participants but by other parties. In the recent years, however, it also can be observed that, particularly, the large American platforms, such as Coursera and Udacity, often deviate from their originally stated goals and offer more and more paid-for content.

If you are interested in the topic of the cost of MOOCs, these articles might offer further insight to it:

| MOOCS: Expectations and Reality A 200-page report by the Center for Benefit-Cost Studies of Education from the Columbia University. It focuses on reasons of how and why institutions engage in MOOCs. The six major goals (Extending Reach and Access, Building and Maintaining the Brand, Improving Economics, Improving Educational Outcomes, Innovation in Teaching and Learning, Research on Teaching and Learning) are discussed in theory and on the basis of 13 cases. Link to the Report |

| Resource Requirements and Costs of Developing and Delivering MOOCs An Academic Paper of Brown University and Yale university that focuses exclusively on the cost of MOOCs Link to the paper |

| Revenue vs. Cost of MOOC platforms A research paper by authors from TU Dresden, TU Graz and Uni Graz that analyses different business models for MOOC platforms and presents a cost model of the Austrian iMooX platform. Link to the paper |

5.2. Some general numbers

To better understand the possible revenue models, it might be helpful to know about the current scale of enrolments, courses, and participants. The following numbers have been taken from Class Centrals annual MOOC report in 2017 (Shah 2017). In 2017, 23 million new learners signed for a MOOC, the total number of registered learners is now 81 million. The share of Coursera, as the largest platform is 30 million registered users, followed by edX with 14 million, XuetangX with 9.3 million, Udacity with 8 million, and FutureLearn with 8 million. Some of these, however, might be duplicates, as many learners have registered in several of these platforms. In total, 9,400 courses have been created by about 800 universities worldwide, so far.

5.3. Possible revenues at a MOOC level for the content provider

One could argue that MOOCs themselves should generate additional revenue streams that compensate for the development and operational cost. As such, all additional services that can be derived from MOOCs’ free offerings can be:

- Formal certificates

- Statements of participation

- Individual coaching / tutoring during the MOOC

- Tailored courses for employees as part of a professional development training (e.g., Small Private Online Course (SPOC) based on a MOOC)

- Tailored (paid-for) follow-up resources based on participants’ data in MOOC

- Remedial courses

- Offer ECTS or other HEI-credit points in MOOCs

- Training people who need specific qualifications to access higher education

Note that these services can be either executed by the content provider, the distribution party (platform) separately or together.

Currently, the majority of the content providers are HEIs. However, other content providers are emerging.

- Global enterprises: SAP is offering close to 200 MOOCs on their own platform openSAP since 2013, the German Telekom has been offering MOOCs early on, Google cooperated with Udacity to offer MOOCs, etc. The motivation why these courses are offered are training (future) employees, training customers how to use certain products, courses with a corporate social responsibility background, marketing, etc. In many of these cases the MOOCs are replacing or supplementing existing other (educational) instruments and create revenue by reducing the costs that would incur if traditional methods would be used.

- Small and Medium Enterprises (SMEs): due to the smaller size of these companies, to produce a MOOC, in general, is not the right tool to provide training for employees, depending on the product, however, it might quite well be the right tool to train customers. Also, as a marketing tool or to attract new employees, it might be the proper choice. Examples for SMEs that successfully make use of this option are e.g. Signavio or msg Systems AG, which are providing MOOCs for their customers and a general public on the mooc.house platform.

- International organizations and NGOs: the World Wildlife Fund (WWF) and the German Climate Consortium (DKK) have created a MOOC, which is available for the general public on the platforms mooin and openSAP. The World Health Organization (WHO) is running their own MOOC platform, OpenWHO, to provide courses for their first responders and the affected public in case of pandemic outbreaks.

5.4. Possible revenues and benefits for an educational institution

As listed in Table 2 under the row “non-direct monetary drivers”, an HEI may invest in MOOCs if other benefits at an institutional level justify the cost of MOOCs. As such, the MOOC operation is connected to the business model at an institutional level. Possible reasons and drivers behind it might be:

- MOOC as a marketing model

- MOOCs to attracts better and/or more (on-campus) students

- To attract new kinds of students

- Innovation on educational provision

- Develop scalable educational services

- Improve the quality of on-campus education

- Reduce the cost of the regular course provision

- MOOCs as a research area: educational models, scalable web technologies, machine learning, mobile applications, etc.

According to many U.S. and European studies, the most dominant objective for educational institutions to be involved in MOOCs is to increase their institution’s visibility and to develop better reputation. In addition, institutions in these continents indicate that using MOOCs as an innovation area (e.g. improve quality of on-campus offering, contribute to the transition to more flexible and online education, improve teaching) and responding to the demands of learners and societies are important objectives as well. Consequently, the possible revenue streams are related to these objectives as well. Another model that has been emerging in the last two or three years are MOOCs for online programs. Georgia Tech, Arizona State, University of Illinois, e.g. are offering online programs on Coursera, Udacity, or edX: Master of Science in Computer Science. The price of these courses ranges between $7000 and $17000, which is cheap compared to the same programs offered on-site and attracts a new clientele of students. Several other universities are offering similar programs in a wide range of subjects (Shah 2017a).

5.5. Revenues and Costs of MOOC platforms

There are not many empirical data on detailed costs, funding and revenue structures of MOOC platforms. The distribution of a fully produced online course has almost zero marginal cost (At least according to Anant Agarwal’s keynote on the EMOOCs conference 2016. The emphasis of this statement has to be put on „marginal“.), rather, services such as the platform development, course integration, analysis, branding etc. account for the largest part of the total cost.

5.5.1. Funding

The big MOOC platforms are usually either publicly funded (e.g. FUN) or financed by a model that is leveraged with equity capital and/or venture capital (e.g. Coursera, iversity). Private (e.g. companies) or public investors (e.g. foundations) supported various providers through substantial investments (partially in the double-digit million euro range) in that stage. It can be assumed that these investments were mainly used for the establishment of technical infrastructure, business cooperation and market position. Hence, the platform providers must generate turnover with increasing establishment on the market in order to pay returns to the investors. In 2016, the German platform iversity was on the brink of bankruptcy and had to change its mode of operations completely after having been rescued by the Holtzbrinck publishing group (Lomas 2016). Class Central reports that Udacity’s revenues in 2017 reached $70 million and it still is not profitable. Udacity was the only platform that has revealed its revenues to the public. Class Central estimated Coursera’s revenues for 2017 at close to $100 million (Shah 2017c). But how do MOOC providers make revenues?

5.5.2. Revenues B2C

MOOC participants may be willing to pay for the following additional services by a MOOC platform provider (business-to-consumer/B2C):

- Issuing Certifications

- Issuing paid Statement of Participations

- Donations

- “Specializations” (“Specializations” feature a sequence of courses (typically four to six) with a capstone project where students apply the skills learned in order to earn a certificate. Launched two years ago, the programme appears successful given the number of Specializations offered—in the hundreds according to Coursera. Fees range between $300 and $600. Tuition is determined by the price of each course (which range between $39 and $79), the number of courses within each, and the fee for the capstone project. If there is even modest student demand for Specializations as Coursera founder Daphne Koller indicates, revenue opportunity is significant (Bogen, 2015).), Course Curricula

- Purchase Courses for assignments with free audit

Typically, the revenues are shared with the content provider in a pre-defined revenue share.

5.5.3. Revenues B2B

part from generating revenue at a B2C level, MOOC platforms and other providers around it offer educational and other services around the product of the MOOC. At this moment, institutions pay those providers for the services such as:

- Course Production Services

- MOOC platform fees for hosting content

- Global marketing and branding

- Learning analytics tools

- Translation services

- Certification services

- Recruiting Services for companies and other organisations (E.g. Coursera charged companies a flat fee for introductions to matched students. The revenue would be shared with the HEI whose courses the student had registered for. At launch, positions were limited to Software Engineering and initial companies using the service included Facebook, Twitter, AppDirect, and TrialPay).

- Further services for the professional development process of an organisation (customer relationship management, webinars, course moderation) etc.

- Training and consulting on how to design/develop MOOCs

- Using (anonymised) data for recruitment

Most elements in this business-to-business (B2B) model are related to the MOOC platform providing paid services to mainly higher educational institutions or corporates. Corporate training is getting increasingly relevant, as more organisations use MOOCs for their professional development activities. This model focuses on the training or human resources development needs of corporates. In other words, MOOC providers charge corporations by the number of employees participating in courses or further services they may need. This model also targets the participants who would like to improve their skills. Corporates often foster the use of MOOCs for professional development activities due to their higher flexibility and lower cost structure compared to onsite training.

6. Possible future trends

6.1. Will MOOCs be for free?

As an increasing number of stakeholders gets involved in the creation of MOOCs, there might be a trend of greater diversification of the services around and beyond the MOOC itself. The percentage of organisations (companies, and public) who use MOOCs as part of their professional development training will probably be increasing. At least some providers have a trend to start moving to paid-for courses. Whether the courses by other providers will remain free of charge for this purpose is unclear though. Depending on the target groups (students, lifelong learners, employees etc.), there might be price discrimination or product differentiation with additional services for MOOCs.

6.2. Increased unbundling of Education

Universities typically offer a bundle package including a range of services such as teaching, assessment, accreditation and student facilities to all learners, whether they require them or not. MOOCs are opening up a discussion around the unbundling of such services. Unbundling means that parts of the process of education are not provided by one, but several providers, or that some parts are outsourced to specialised institutions and providers. Regular examples are support of the study choice process, study advice and tutoring, content creation and development, examination training, assessment and proctoring, learning platforms, learning analytics services, etc.

As such, different educational services are split amongst different funding schemes and even different customer segments. Some (educational) services are outsourced to third parties for concerns such as cost efficiency or organisational priorities. As such, different educational services are unbundled. Freemium business models depend on the money that is generated from additional services to be paid for next to the basic product – service offered for free.

MOOCs are seen as an accelerator of these unbundling processes by outsourcing the marketing efforts, ICT/delivery platform, exams, learning analytics services, etc. Consequently, the business model of MOOCs (and education) will change as well.

6.3. Increased internationalisation of the MOOC market

In current evaluations often, only the US American platforms and their business models are considered. Sometimes, at least the larger European players, such as FutureLearn are taken into account. However, there is a quickly growing number of MOOC providers in countries where English is not the first language.

In France the government operates the platform FUN, OpenClassrooms (https://openclassrooms.com/) is a private player that is active since quite some time. In Italy the government recently has started the EduOpen (http://www.eduopen.org/) platform in cooperation with several Italian universities and some commercial technology providers. In Germany there are openHPI (https://open.hpi.de/), openSAP ( https://open.sap.com/), mooin (https://www.oncampus.de/mooin), in Austria there is iMOOX (https://imoox.at/mooc/). MiriadaX (https://miriadax.net/home) is one of the largest MOOC platforms in the world serving a Spanish speaking audience. Edraak (https://www.edraak.org/en/) founded and funded by the Queen Rania Foundation serves the Arab world with courses from its base in Jordan. Campus (https://campus.gov.il/), the platform operated by the Israeli government offers courses in Hebrew, Arab, and English. In China there are XuetangX (http://www.xuetangx.com/) and iCourse163 (https://www.icourse163.org/), India recently started its own platform Swayam (https://swayam.gov.in/), IndonesiaX (https://www.indonesiax.co.id/) in Indonesia, etc.

7. Conclusions

Despite the fact that Massive Open Online Courses (MOOCs) are offering a complete course free of charge by definition, there are monetary costs and benefits associated with it. Several stakeholders are associated with the creation and the distribution of MOOCs as well as research and further services beyond the course itself. The diversity of MOOCs and players behind it makes it thus difficult to apply a universal business model to MOOCs. Currently, a successful and financially sustainable business model of MOOC has yet to be developed. Since MOOCs are free of charge, services around MOOCs and additional values (e.g. certification) are offered in order to create revenue. The whole cost-revenue cycle is even more complex since most content providers cross-finance their costs and many MOOC platforms receive external funding for their activities. The rapid growth in the MOOC market leads to the influx of new stakeholders, bringing in new services, sponsorships, customers, cross-financing models etc. in the whole world of MOOCs. Currently, there is also a trend towards an increasing number of corporations using MOOCs or the format of MOOCs for professional development activities, which might not only increase the revenues and business opportunities in the market substantially, but also challenge the open education approach. However, some MOOC platforms (e.g., FUN) tries to tackle this by providing SPOCs based on MOOCs.

Note

References

Alario-Hoyos, C., Pérez-Sanagustín, M., Cormier, D., Delgado-Kloos, C. (2014). “Proposal for a conceptual framework for educators to describe and design MOOCs”, Journal of Universal Computer Science (JUCS) (Vol. 20, No. 1 pp. 6-23)</p

Al-Debei, M. M., El-Haddadeh, R., & Avison, D. (2008). “Defining the business model in the new world of digital business.” In Proceedings of the Americas Conference on Information Systems (AMCIS) (Vol. 2008, pp. 1-11).

Fielt, E. (2013). “Conceptualising Business Models: Definitions, Frameworks and Classifications”. Journal of Business Models (Vol. 1, No. 1 pp. 85-105)

H. Fischer, S. Dreisiebner, O. Franken, M. Ebner, M. Kopp, T. Köhler (2014). “Revenue vs. Costs of MOOC platforms. Discussion of Business Models for xMOOC Providers, Based on Empirical Findings and Experiences During Implementation of the Project iMoox” (pp. 2991-3000), ICERI2014 Proceedings, 7th International Conference of Education, Research and Innovation, Seville (Spain) 17-19 November, 2014: IATED.

Hollands, F.M., Tirthali, D. (2014). Research Requirements and Costs of Developing and Delivering MOOCs. The International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning, 15(5). Retrieved from: http://www.irrodl.org/index.php/irrodl/article/view/1901/3069

Lomas, N. (2016) Online learning platform iversity gets a lifeline from Holtzbrinck media group

Retrieved from https://techcrunch.com/2016/08/09/online-learning-platform-iversity-gets-a-lifeline-from-holtzbrinck-media-group/?guccounter=19

Osterwalder, A. (2004). The Business Model Ontology – A Proposition In A Design Science Approach. PhD thesis University of Lausanne http://www.hec.unil.ch/aosterwa/PhD/Osterwalder_PhD_BM_Ontology.pdf

Osterwalder, A., & Pigneur, Y. (2010) Business model generation: A handbook for visionaries, game changers, and challengers. New York, NY: Wiley. See also http://www.businessmodelgeneration.com/

Shah, D. (2017a) By The Numbers: MOOCS in 2017

Retrieved from https://www.class-central.com/report/mooc-stats-2017/

Shah, D. (2017b) Udacity’s Revenues Reach $70 Million in 2017

Retrieved from https://www.class-central.com/report/udacity-revenues-2017/

Shah, D. (2017c) Coursera’s 2017: Year in Review

Retrieved from https://www.class-central.com/report/coursera-2017-year-review/

Stacey, P. (2015) Traditional Economics Don’t Make Sense for Open Business Models. Blog retrieved from https://medium.com/made-with-creative-commons/traditional-economics-don-t-make-sense-for-open-business-models-d277428535e0#.kl72wz9de

UNESCO-COL (2016). Making Sense of MOOCs: A Guide for Policy-Makers in Developing Countries. Retrieved from http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0024/002451/245122E.pdf

Yoram M. Kalman (2014) “A race to the bottom: MOOCs and higher education business models“ In Open Learning: The Journal of Open, Distance and e-Learning (Vol. 29, Issue. 1)